Here is another mushroom story! Interestingly enough, this one is about a rather peculiar kind of mushroom; the “Bird’s nest fungus”. I had already heard of this mushroom (or read about it somewhere) by the time I was learning different forms of mushrooms for my “Microbial Life” course practicals in the second year at university. It was really around that time that I developed a curiosity and amazement toward how diversely formed mushrooms are. I remember seeing charismatic earthstars, phallic stinkhorns, squishy jelly fungi, and weird puffballs during that lab class and thinking “ Whoah, how weird can a mushroom be”. After that lab, it became my habit to deliberately examine the diversity and individuality of each mushroom that I come across. It also became my habit to photograph the mushrooms that I find in my backyard, and also to go hunting for them whenever the climate is right (I am truly blessed to have had a comparatively large unmodified backyard at my house, still preserved in its natural ecological state, within the rapidly urbanizing village where I live).

Anyhow, one day, while I was mushroom hunting in my backyard, ever so randomly, I came across just a single bird’s nest mushroom, hidden in the leaf litter, lodged onto a tiny twig for its dear life. This find was surely serendipitous since it’s almost impossible to detect something that small, the way I did at that moment. It’s the first time that I’ve seen a bird’s nest fungus in the wild, and the truth be told, I wasn’t even aware at the time that this mushroom was in Sri Lanka. Those days, I was engaged in my undergraduate research, which involved culturing lots and lots of mushrooms. So I tried my best to make a culture of it but unfortunately, nothing grew on my culture plates!

A lone survivor! The first bird’s nest that I encountered. Almost all of the peridioles are splashed out. There are some structures resembling disintegrated fruiting bodies around it. Unfortunately, I haven’t placed a reference object but the green stuff around it is Calymperes moss, so you can gauge the size roughly.

Eventually, the bird’s nest was forgotten since it wasn’t pertinent to the topic I was working on, which was edible mushrooms, and the bird’s nest mushroom is hardly edible. But later on, about a year later, this mushroom presented itself to me again, this time, in the garden of my university. And not just one nest, but a whole lot of fruiting bodies sitting on a cut-down tree stump! I was delighted. On this occasion, I did some research on the specific culturing techniques of it and managed to obtain a pure culture, finally!

So apparently, to spot certain bird’s nests, treetops aren’t the best place to look for. Sometimes, in forest floors, on decaying wood or debris, inconspicuous mycological wonders lie utterly unnoticed. One such Basidiomycete group, which strays way off from the usual “cap and stipe” cliché of mushrooms, is the “Bird’s Nest Fungi”. “Bird’s nest fungi” is a catchall term for several species that are included within the family Nidulariaceae of the order Agaricales. The fruiting bodies of the genera Cyathus, Crucibulum, Mycocalia, Nidula and Nidularia are basically categorized under the bird’s nest fungi. Their curious and absurd form, which resembles tiny bird nests, makes them one of the most fascinating groups of fungi in nature.

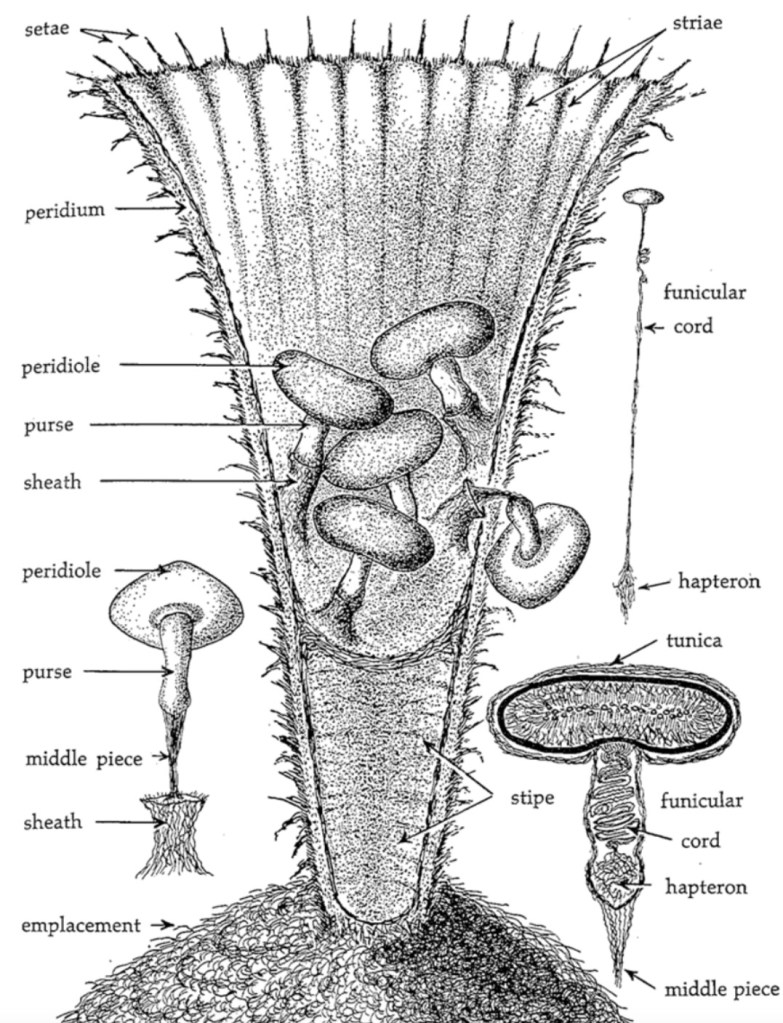

The cup/nest structure, termed as the ‘Peridium’, is usually around 1 cm tall and is sometimes shaggy outside (Eg: Cyathus, Nidula). A thin outer covering known as the ‘Epiphragm’ covers the peridium when young. These miniature versions of bird’s nests come with their own minute version of “eggs” referred to as ‘Peridioles’. These are the blackish-grey, egg/lentil-shaped structures that are stacked inside the nests. They carry basidiospores, the reproductive units of Basidiomycete fungi. Peridioles are connected to the peridium with the aid of a ‘Funicular cord’. This cord usually stays condensed within a ‘Purse’ located below each peridiole. The free end (the end that is not attached to the peridiole) of this cord forms an adhesive pad called the ‘Hapteron’ and joins with the inner peridium (please refer to the diagram to guide yourself through all these terms).

These minuscule bird’s nests are not just about the looks but in fact, they serve a functional purpose. Martin (1927) discussed for the first time how the peridium functions as a splash cup to disperse the peridioles out of the nest. When raindrops splash on the cup, the hydraulic pressure causes the peridioles to be dislodged from the peridium and just like that, they finally leave the nest! They are splashed out, all the while untangling the condensed 10 cm long tail behind them. Upon contact with a substrate (usually foliage), the funicular cord entangles with it while adhering the peridioles to the substrate through the sticky hapteron, where the basidiospores germinate.

Apart from being saptrotrophic fungal decomposers of nature, and being visually ingenious, they don’t hold much importance. However, certain scientific studies were able to uncover some potential uses for these fascinating bird’s nests. Some were found to possess rather important bioactive compounds that have medicinal and biocontrol properties. Many studies have revealed the ability of Cyathus spp. in controlling several soil-borne plant pathogenic fungi including Fusarium spp. and Pythium aphanidermatum through antagonism (antagonism is when a fungus interferes/oppresses the growth and activity of another pathogenic fungus). Bird’s nest fungi were also reported to be particularly effective degraders of lignocellulosic material, proving to be potential candidates for industrial use in the bio pulping and the animal feed industries.

Coming to the end of this account, I cannot help but reminisce these words of Lady Galadriel from The Lord of the Rings, which goes as “Even the smallest person can change the course of the future.” Well, that clearly is the case for me, as these tiniest of the mushrooms definitely have changed my perspective of how I view the grandeur of mother nature. That is simply why these exquisite mycological wonders are totally MyCuppaTea.

Reference texts:

Martin, G. (1927). Basidia and Spores of the Nidulariaceae. Mycologia, 19(5), pp.239-247.

Sethuraman, A., Akin, D., Eisele, J. and Eriksson, K. (1998). Effect of aromatic compounds on growth and ligninolytic enzyme production of two white rot fungi & Ceriporiopsis subvermispora; and Cyathus stercoreus;. Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 44(9), pp.872-885.

Sutthisa, W. (2018). Biological Control Properties of Cyathus spp. to Control Plant Disease Pathogens. Journal of Pure and Applied Microbiology, 12(4), pp.1755-1760.

Brodie, H. J. 1975. The bird’s nest fungi. Univ. Toronto Press. Toronto, Toronto, Ont. 199 p.

Lengthy but very educative. Wonderful piece of writing

LikeLiked by 1 person